Wesley Mission partners with the ACT Government to deliver nearly 100 affordable housing units in Canberra, providing safe, secure homes for those in need.

News and stories

Select your category

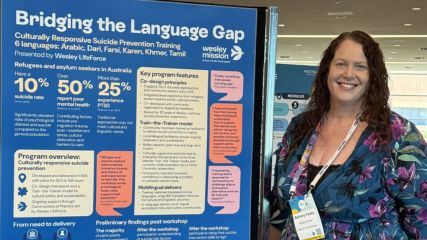

Discover how Wesley Mission is pioneering a culturally informed approach to refugee suicide prevention, addressing stigma and building hope through connection and community-led support.

The Escaping Violence Payment (EVP) trial is no longer accepting new applications. From 1 July 2025, the new Leaving Violence Program will support people experiencing intimate partner violence with...

Murdoch students, with Wesley LifeForce's support, are transforming campus mental health through the Murdoch Life Assist suicide prevention network.

Wesley LifeForce’s Coffs Coast network offers suicide prevention training, support events like Fluro Friday & vital community connection in Coffs Harbour.

Local action is saving lives in rural Victoria, where a suicide prevention network is helping an isolated community support its own.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Suicide Prevention Training program addresses disproportionately high suicide rates for Indigenous Australians.

The blue tractor is a reminder for anyone who sees it to reach out for help and to connect with support services.

Wesley LifeForce’s Suicide Prevention workshops are creating more resilient, supportive communities and 95% of participants highly recommend program.

SBS Translation Services and Wesley LifeForce have joined forces to help prevent suicide among refugee and asylum-seeker communities in Australia.

The network is now seeking funding to refurbish an existing youth centre to help prevent suicide among young people.

Held at the central park in Strathalbyn, ‘Music in the Park’ has created a space for people in the community to connect while listening to local artists.